Composers

Ernst Krenek (August 23, 1900 – December 22, 1991) was an Austrian of Czech origin and, from 1945, American composer. He explored atonality and other modern styles and wrote a number of books, including Music Here and Now (1939), a study of Johannes Ockeghem (1953), and Horizons Circled: Reflections on my Music (1974). Krenek wrote two pieces using the pseudonym Thornton Winsloe.

Krenek was born in Vienna as the son of a Czech soldier in the Austro-Hungarian army. Throughout his life, however, he insisted that his name be written Krenek rather than his father's Křenek, and that it should be pronounced as a German word. He studied there and in Berlin with Franz Schreker before working in a number of German opera houses as conductor. During World War I, Krenek was drafted into the Austrian army, but he was stationed in Vienna, allowing him to go on with his musical studies. In 1922 he met Alma Mahler, wife of the late Gustav Mahler, and her daughter, Anna, whom he married in March 1924. That marriage ended in divorce before its first anniversary.

At the time of his marriage to Anna Mahler, Krenek was completing his Violin Concerto No. 1, Op. 29. The Australian violinist Alma Moodie assisted Krenek, not with the scoring of the violin part, but with getting financial assistance from her Swiss patron Werner Reinhart at a time when there was hyper-inflation in Germany. In gratitude, Krenek dedicated the concerto to Moodie, and she premiered it on 5 January 1925, in Dessau. Krenek’s divorce from Anna Mahler became final a few days after the premiere. Krenek did not attend the premiere, but he did have an affair with Moodie, which has been described as "short-lived and complicated". He never managed to hear her play the concerto, but he did "immortalize some aspects of her personality in the character of Anita in his opera Jonny spielt auf". In 1924, Krenek also dedicated his Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 33 to Alma Moodie, and his Kleine Suite, Op. 28 (1924) to Reinhart.

His journalism was banned and his music was targeted in Germany by the Nazi Party beginning in 1933. On March 6, one day after elections in which the Nazis gained control of the Reichstag, Krenek's incidental music to Goethe's Triumph der Empfindsamkeit was withdrawn in Mannheim, and eventually pressure was brought to bear on the Vienna State Opera, which cancelled the commissioned premiere of Karl V. The jazz imitations of Jonny spielt auf were included in the 1938 Degenerate art exhibition in Munich. Nonetheless, despite protests by conservatives and the fledgling Nazi party, that work was a great success in Krenek's lifetime, playing all over Europe and becoming so popular that even a brand of cigarettes, still on the market today in Austria, was named "Jonny".

In 1938 Krenek moved to the United States of America, where he taught music at various universities, the first being Vassar College. He later taught at other institutions including Hamline University in Saint Paul, Minnesota from 1942-1947. There he met and married his third wife, his student and composer Gladys Nordenstrom. He became an American citizen in 1945. He later moved to Toronto, Canada where he taught at The Royal Conservatory of Music during the 1950s. His students included Milton Barnes, Lorne Betts, Samuel Dolin, Robert Erickson, Halim El-Dabh, Richard Maxfield, Will Ogdon, and George Perle. He died in Palm Springs, California. In 1998 Gladys Nordenstrom founded the Ernst Krenek Institute and in 2004 the private foundation Krems die Ernst Krenek in Vienna, Austria.

After meeting Krenek in 1922, Alma Mahler asked him to complete her late husband's Symphony No. 10. Krenek assisted in editing the first and third movements but went no further. More fruitful was Krenek's response to an approximately contemporary request from his pianist and composer friend Eduard Erdmann, who wished to add Schubert's Reliquie piano sonata to his repertoire, for completions of that work's fragmentary third and fourth movements. Krenek's completion, dated to 1921 in some sources but to 1922 in his own memory, later found other champions in Webster Aitkin in the concert hall and Ray Lev and Friedrich Wührer on records.

In his notes to the Lev recording, dated July 1947, Krenek offered insights into the challenges of completing another composer's works in general and the Schubert sonata in particular.

Completing the unfinished work of a great master is a very delicate task. In my opinion it can honestly be undertaken only if the original fragment contains all of the main ideas of the unfinished work. In such a case a respectful craftsman may attempt, after an absorbing study of the master's style, to elaborate on those ideas in a way which to the best of his knowledge might have been the way of the master himself. The work in question will probably have analogies among other, completed works of the master, and careful investigation of his methods in similar situations will indicate possible solutions of the problems posed by the unfinished work. Even then the artist who goes about the ticklish task will feel slightly uneasy, knowing from his own experience as a composer that the creative mind does not always follow its own precedents. He is more conscious of the fact that unpredictability is one of the most jealously guarded prerogatives of genius. … However, scruples of this kind may be set aside once we are certain that the author of the fragment has put forth the essential thematic material that was expected to go into the work. If this is not the case, I feel that no one, not even the greatest genius, should dare to complete the fragments left by another genius."

As an example, Krenek explains that a careful student of Rembrandt's style might be able to complete a painting lacking one or two corners but could never supply two entirely missing paintings from a four-painting series; such an attempt would result only in "more or less successful fakes." Turning to a musical example, Krenek, evidently unaware of the surviving sketch of a third movement, avers that Schubert's own "Unfinished" Symphony "was left by its creator with only two of its four movements written; of the other two there is no trace. It would be possible to write two or more movements to the symphony in the manner of Schubert, but it would not be Schubert."

Krenek's music encompassed a variety of styles and reflects many of the principal musical influences of the 20th century.

His early work is in a late-Romantic idiom, showing the influence of his teacher Franz Schreker.

Around 1920 he turned to atonality, under the influence of Ernst Kurth's textbook, Lineare Kontrapunkt, and the tenets of Busoni, Schnabel, Erdmann, and Scherchen, amongst others.

A visit to Paris, during which he became familiar with the work of Igor Stravinsky (Pulcinella was especially influential) and Les Six, led him to adopt a neo-classical style around 1924.

Shortly afterward, he turned to neoromanticism and incorporated jazz influences into his opera Jonny spielt auf (Jonny Strikes Up, 1926) and one-act opera Schwergewicht (1928). Other neoromantic works of this period were modeled on music of Franz Schubert, a prime example being Reisebuch aus den österreichischen Alpen (1929).

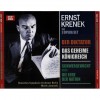

Krenek abandoned the neoromantic style in the late 1920s to embrace Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique,the method exclusively employed in Krenek's opera Karl V (1931–33) and most of his later pieces.His most uncompromising use of the twelve-tone technique was in his Sixth String Quartet (1936) and his Piano Variations (1937). In the Lamentatio Jeremiae prophetae (1941–42) Krenek combined twelve-tone writing with techniques of modal counterpoint of the Middle Ages.

In 1955 he was invited to work in the electronic music studio at WDR in Cologne, and this experience motivated him to develop a serial idiom.

Beginning around 1960 he added to his serial vocabulary some principles of aleatoric music, in works such as Horizon Circled (1967), From Three Make Seven (1960–61), and Fibonacci-Mobile (1964).

In his later years his compositional style became more relaxed, though he continued to use elements of both twelve-tone and serial techniques.

Recently Added

Biography

Ernst Krenek (August 23, 1900 – December 22, 1991) was an Austrian of Czech origin and, from 1945, American composer. He explored atonality and other modern styles and wrote a number of books, including Music Here and Now (1939), a study of Johannes Ockeghem (1953), and Horizons Circled: Reflections on my Music (1974). Krenek wrote two pieces using the pseudonym Thornton Winsloe.

Krenek was born in Vienna as the son of a Czech soldier in the Austro-Hungarian army. Throughout his life, however, he insisted that his name be written Krenek rather than his father's Křenek, and that it should be pronounced as a German word. He studied there and in Berlin with Franz Schreker before working in a number of German opera houses as conductor. During World War I, Krenek was drafted into the Austrian army, but he was stationed in Vienna, allowing him to go on with his musical studies. In 1922 he met Alma Mahler, wife of the late Gustav Mahler, and her daughter, Anna, whom he married in March 1924. That marriage ended in divorce before its first anniversary.

At the time of his marriage to Anna Mahler, Krenek was completing his Violin Concerto No. 1, Op. 29. The Australian violinist Alma Moodie assisted Krenek, not with the scoring of the violin part, but with getting financial assistance from her Swiss patron Werner Reinhart at a time when there was hyper-inflation in Germany. In gratitude, Krenek dedicated the concerto to Moodie, and she premiered it on 5 January 1925, in Dessau. Krenek’s divorce from Anna Mahler became final a few days after the premiere. Krenek did not attend the premiere, but he did have an affair with Moodie, which has been described as "short-lived and complicated". He never managed to hear her play the concerto, but he did "immortalize some aspects of her personality in the character of Anita in his opera Jonny spielt auf". In 1924, Krenek also dedicated his Sonata for Solo Violin, Op. 33 to Alma Moodie, and his Kleine Suite, Op. 28 (1924) to Reinhart.

His journalism was banned and his music was targeted in Germany by the Nazi Party beginning in 1933. On March 6, one day after elections in which the Nazis gained control of the Reichstag, Krenek's incidental music to Goethe's Triumph der Empfindsamkeit was withdrawn in Mannheim, and eventually pressure was brought to bear on the Vienna State Opera, which cancelled the commissioned premiere of Karl V. The jazz imitations of Jonny spielt auf were included in the 1938 Degenerate art exhibition in Munich. Nonetheless, despite protests by conservatives and the fledgling Nazi party, that work was a great success in Krenek's lifetime, playing all over Europe and becoming so popular that even a brand of cigarettes, still on the market today in Austria, was named "Jonny".

In 1938 Krenek moved to the United States of America, where he taught music at various universities, the first being Vassar College. He later taught at other institutions including Hamline University in Saint Paul, Minnesota from 1942-1947. There he met and married his third wife, his student and composer Gladys Nordenstrom. He became an American citizen in 1945. He later moved to Toronto, Canada where he taught at The Royal Conservatory of Music during the 1950s. His students included Milton Barnes, Lorne Betts, Samuel Dolin, Robert Erickson, Halim El-Dabh, Richard Maxfield, Will Ogdon, and George Perle. He died in Palm Springs, California. In 1998 Gladys Nordenstrom founded the Ernst Krenek Institute and in 2004 the private foundation Krems die Ernst Krenek in Vienna, Austria.

After meeting Krenek in 1922, Alma Mahler asked him to complete her late husband's Symphony No. 10. Krenek assisted in editing the first and third movements but went no further. More fruitful was Krenek's response to an approximately contemporary request from his pianist and composer friend Eduard Erdmann, who wished to add Schubert's Reliquie piano sonata to his repertoire, for completions of that work's fragmentary third and fourth movements. Krenek's completion, dated to 1921 in some sources but to 1922 in his own memory, later found other champions in Webster Aitkin in the concert hall and Ray Lev and Friedrich Wührer on records.

In his notes to the Lev recording, dated July 1947, Krenek offered insights into the challenges of completing another composer's works in general and the Schubert sonata in particular.

Completing the unfinished work of a great master is a very delicate task. In my opinion it can honestly be undertaken only if the original fragment contains all of the main ideas of the unfinished work. In such a case a respectful craftsman may attempt, after an absorbing study of the master's style, to elaborate on those ideas in a way which to the best of his knowledge might have been the way of the master himself. The work in question will probably have analogies among other, completed works of the master, and careful investigation of his methods in similar situations will indicate possible solutions of the problems posed by the unfinished work. Even then the artist who goes about the ticklish task will feel slightly uneasy, knowing from his own experience as a composer that the creative mind does not always follow its own precedents. He is more conscious of the fact that unpredictability is one of the most jealously guarded prerogatives of genius. … However, scruples of this kind may be set aside once we are certain that the author of the fragment has put forth the essential thematic material that was expected to go into the work. If this is not the case, I feel that no one, not even the greatest genius, should dare to complete the fragments left by another genius."

As an example, Krenek explains that a careful student of Rembrandt's style might be able to complete a painting lacking one or two corners but could never supply two entirely missing paintings from a four-painting series; such an attempt would result only in "more or less successful fakes." Turning to a musical example, Krenek, evidently unaware of the surviving sketch of a third movement, avers that Schubert's own "Unfinished" Symphony "was left by its creator with only two of its four movements written; of the other two there is no trace. It would be possible to write two or more movements to the symphony in the manner of Schubert, but it would not be Schubert."

Krenek's music encompassed a variety of styles and reflects many of the principal musical influences of the 20th century.

His early work is in a late-Romantic idiom, showing the influence of his teacher Franz Schreker.

Around 1920 he turned to atonality, under the influence of Ernst Kurth's textbook, Lineare Kontrapunkt, and the tenets of Busoni, Schnabel, Erdmann, and Scherchen, amongst others.

A visit to Paris, during which he became familiar with the work of Igor Stravinsky (Pulcinella was especially influential) and Les Six, led him to adopt a neo-classical style around 1924.

Shortly afterward, he turned to neoromanticism and incorporated jazz influences into his opera Jonny spielt auf (Jonny Strikes Up, 1926) and one-act opera Schwergewicht (1928). Other neoromantic works of this period were modeled on music of Franz Schubert, a prime example being Reisebuch aus den österreichischen Alpen (1929).

Krenek abandoned the neoromantic style in the late 1920s to embrace Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique,the method exclusively employed in Krenek's opera Karl V (1931–33) and most of his later pieces.His most uncompromising use of the twelve-tone technique was in his Sixth String Quartet (1936) and his Piano Variations (1937). In the Lamentatio Jeremiae prophetae (1941–42) Krenek combined twelve-tone writing with techniques of modal counterpoint of the Middle Ages.

In 1955 he was invited to work in the electronic music studio at WDR in Cologne, and this experience motivated him to develop a serial idiom.

Beginning around 1960 he added to his serial vocabulary some principles of aleatoric music, in works such as Horizon Circled (1967), From Three Make Seven (1960–61), and Fibonacci-Mobile (1964).

In his later years his compositional style became more relaxed, though he continued to use elements of both twelve-tone and serial techniques.